|

There are several new grants of interest. No. 22-0065/NA. U.S. v. Willie C. Jeter. CCA 201700248. On further consideration of the petition for grant of review, the briefs filed by the parties, and oral argument, it is ordered that said petition is granted on the following specified issues: I. IN UNITED STATES v. CRAWFORD, 15 C.M.A. 31, 35 C.M.R. 3 (1964), THIS COURT HELD THAT IN THE COURSE OF PANEL SELECTION A RACE CONSCIOUS PROCESS IS PERMISSIBLE FOR THE PURPOSE OF INCLUSION. HOW DOES THE CRAWFORD DECISION AFFECT THE ANALYSIS OF THIS CASE UNDER AVERY v. GEORGIA, 345 U.S. 559 (1953)? II. IN LIGHT OF APPELLANT'S STATEMENT AT ORAL ARGUMENT THAT RACE IS AN IMPROPER CONSIDERATION IN DETAILING PANEL MEMBEMEMBERS, SHOULD COURT OVERRULE UNITED STATES v. CRAWFORD, 15 C.M.A. 31, 35 C.M.R. 3 (1964)? (Emphasis added.) The case was tried in 2017, NMCCA affirmed in 2019, CAAF summarily vacated the opinion in 2020 with a remand for review in light of United States v. Bess. In Octobter 2021, NMCCA We find that the convening authority did not violate Appellant’s equal protection or due process rights, and affirm on this AOE. We further adopt our holdings on AOEs II-XI, consistent with this Court’s prior published opinion in Jeter I and once again conclude the findings and sentence are correct in law and fact and that no error materially prejudiced Appellant’s substantial rights. No. 22-0237/AF. U.S. v. Caleb A.C. Smith. CCA 40013. On consideration of the petition for grant of review of the decision of the United States Air Force Court of Criminal Appeals, it is ordered that said petition is granted on the following issues: I. WHETHER THE MILITARY JUDGE ERRED IN ADMITTING TEXT MESSAGES AND TESTIMONY AS AN EXCITED UTTERANCE RELATED TO THE ALLEGED VICTIM'S BELIEF THAT SHE WAS RAPED WHERE SHE HAD NO MEMORY OF THE EVENTS IN QUESTION. II. WHETHER THE EVIDENCE WAS LEGALLY INSUFFICIENT BECAUSE THE ALLEGED VICTIM WAS CAPABLE OF CONSENTING AND WHERE, EVEN IF SHE WAS NOT CAPABLE OF CONSENTING, APPELLANT REASONABLY BELIEVED THAT SHE DID CONSENT. No. 22-0259/AR. U.S. v. Erick Vargas. CCA 20220168. On consideration of the petition for grant of review of the decision of the United States Army Court of Criminal Appeals on appeal by the United States under Article 62, Uniform Code of Military Justice, 10 U.S.C. § 862 (2018), it is ordered that said petition is granted on the following issue: WHETHER THE ARMY COURT ERRED IN ITS ABUSE-OF-DISCRETION ANALYSIS BY REQUIRING THE MILITARY JUDGE TO CRAFT THE LEAST-DRASTIC REMEDY TO CURE THE DISCOVERY VIOLATION. Another late discovery case. On Friday, March 4, 2022, prior to the start of appellee's contested court martial, the government re-interviewed SPC. During this interview, SPC stated appellee called her a "beauty queen" and kissed her on the forehead 3-4 times" prior to the sexual assault. This was new information, and the government failed to disclose it to the defense. ACCA held that the military judge erred in dismissing with prejudice because a mistrial under R.C.M. 915(a) was an appropriate and a least drastic remedy. No. 22-0249/CG. U.S. v. Fernando M. Brown. CCA 001-69-21. On consideration of the petition for grant of review of the decision of the United States Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals, it is ordered that said petition is hereby granted on the following issue: ARE APPELLANT'S CONVICTIONS UNDER ARTICLE 91 LEGALLY INSUFFICENT WHERE THERE IS AN ABSENCE OF EVIDENCE THAT THE CHARGED CONDUCT OCCURRED IN THE SIGHT, HEARING, OR PRESENCE OF THE ALLEGED VICTIMS WHILE THEY WERE IN THE EXECUTION OF THEIR OFFICE? The Chief’s Mess of USCGC Polar Star had a text message group comprising all the cutter’s senior enlisted personnel to coordinate, maintain camaraderie while in drydock, and pass work-related information. Appellant sent several offensive texts to this group, including the target of each. In one, he sent a photograph of a fellow chief petty officer, adding a crudelydrawn penis and scrotum to his hard hat. In another, he belittled the sexual orientation of a fellow chief petty officer by sending the group a high school yearbook photograph of her, adding the caption, “Voted most likely to steal your bitch.” Pros. Ex. 5 at 1. Finally, he ridiculed a senior chief who was the senior member of the Mess by sending a picture of a scantily-clad man with a large Dallas Cowboys image on his back, adding the caption, “Found out why [the senior chief] missed chiefs call.” Pros. Ex. 9 at 1. The preferral of charges is an important step in movement toward a court-martial. Most of the time there isn't a reason to challenge the preferral. However, history has shown, and United States v. Floyd , __ M.J. ___ (N-M. Ct. Crim. App. 2022), further shows that it is sometimes worth the effort to peer behind the wizard's curtain, talk to the accuser, and compare the "evidence" the accuser reviewed. There also are some lessons for trial counsel. After referral of charges and shortly before trial was set to begin, the trial defense counsel for Appellee moved to dismiss two of the five specifications alleging sexual abuse of a child for defective preferral and discovery violations. Trial defense counsel argued that, at the time of preferral, Charge II, Specification 2 alleged “excessively inflammatory” language that was not supported by evidence. Trial defense counsel further argued that, at the time of preferral, Charge II, Specification 4 was not supported by the evidence reviewed by the accuser. Finally, the trial defense counsel argued that after preferral and during the months leading up to trial, the Government violated its discovery obligations. The Government appeal raises two broad issues, (1) the MJ violated the rules by issuing written findings and conclusions after receiving the notice of appeal, and (2) abuse of discretion in the rulings.

The Court disagrees that it cannot consider the MJ's written ruling, favorably citing United States v. Catano, 75 M.J. 513 (A. F. Ct. Crim. App. 2015). As the third of three points, the Court adds

The accused was convicted by a military judge sitting alone of several offenses. United States v. Rudometkin, No. 22-0105, 2022 WL 3364139 (C.A.A.F. Aug. 15, 2022). After learning that the military judge had been accused of conduct similar to at least one of the offenses of which he had been convicted, the accused filed a motion for a mistrial, alleging that the judge should have disqualified himself because his impartiality might reasonably be questioned. See R.C.M. 902(a).

A different military judge was detailed to conduct a hearing. He assumed, without deciding, that the trial judge should have disqualified himself and, employing the Supreme Court’s three-factor test from Liljeberg v. Health Servs. Acquisition Corp, 486 U.S. 847, 862 (1988), determined Appellant was not entitled to relief. Rudometkin, at *3. In Liljeberg, the Supreme Court noted that the federal disqualification statute, 28 U.S.C. § 455, on which R.C.M. 902 is based, “neither prescribes nor prohibits any particular remedy for a violation of that duty.” 486 U.S. 847, 862 (1988). The Court recognized that Federal Rule of Civil Procedure (Fed. R. Civ. P.) 60(b)(6), “grants federal courts broad authority to relieve a party from a final judgment ‘upon such terms as are just.’” Id. Action under that Rule “should only be applied in extraordinary circumstances.” Id. at 863–64 (cleaned up). In determining whether the judge’s error in refusing to disqualify was an extraordinary circumstance worthy of vacatur, the Supreme Court listed three factors for an appellate court to consider: (1) the risk of injustice to the parties; (2) the risk of injustice in other cases; and (3) “the risk of undermining the public’s confidence in the judicial process. We must continuously bear in mind that, to perform its high function in the best way justice must satisfy the appearance of justice.” Id. at 864. Although the cases reviewed by the CAAF are criminal, rather than civil, it has applied the Supreme Court’s three-factor Liljeberg test in military judicial disqualification cases since at least 2001. See, e.g., United States v. Butcher, 56 M.J. 87, 91 (C.A.A.F. 2001). The CAAF’s explanation of the first factor has transformed from a balancing of equities—the risk of injustice to the parties—to placing a burden on the accused to establish that he personally suffered an injustice from the judge’s failure to disqualify. See United States v. Martinez, 70 M.J. 154, 159 (C.A.A.F. 2011) (the first Liljeberg factor weighed against the appellant because “the record does not support nor has Martinez identified any specific injustice that he personally suffered under the circumstances”). In a more recent case, the CAAF substituted the Martinez finding on the first factor for the factor itself, claiming that the first Liljeberg factor “examines if there is ‘any specific injustice that [the accused] personally suffered.’” United States v. Uribe, 80 M.J. 442, 449 (C.A.A.F. 2021) (quoting Martinez, 70 M.J. at 159). In Rudometkin, the certified issue before the CAAF was whether the military judge erred by failing to grant a mistrial because the trial judge failed to disqualify himself. Rudometkin, at *4. NIMJ filed an amicus brief pursuant to C.A.A.F. R. 26: an interested non-party amicus curiae brief that provides “relevant matter” not already brought to the attention of the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces may be “of considerable help to the Court. An amicus curiae brief that does not serve this purpose burdens the Court, and its filing is not favored.” CAAF R. 26(b). NIMJ argued, inter alia, the Court should not, as it had in the past, apply the Supreme Court’s Liljeberg test for determining prejudice, because that test had been formulated for civil, not criminal, cases. NIMJ insisted the Court was instead required to apply Article 59(a), UCMJ: “[a] finding or sentence … may not be held incorrect on the ground of an error unless the error materially prejudice[d] the substantial rights of the accused.” In other words, the burden was on the Government to show the error was harmless. The CAAF held that the military judge did not abuse his discretion in denying the accused’s motion for mistrial. It acknowledged and explained the amicus brief but declined to address NIMJ’s arguments because “the parties to the case have not challenged [our precedent].” Id. at *5. The Court cited two cases supporting that proposition: “United States v. Long, 81 M.J. 362, 370 (C.A.A.F. 2021) and FTC v. Phoebe Putney Health Sys., Inc., 568 U.S. 216, 226 n.4 (2013). Of course, there was no amicus curiae challenging the parties’ understanding of the law in Long and, in Phoebe, the amicus was not asking the Supreme Court to apply the law but to recognize an exception to the law and apply it to the case at hand. In Rudometkin, NIMJ was merely asking the CAAF to apply the law mandated by Congress in the UCMJ. And if the judges desired the parties’ inputs, they could have specified that issue and asked the parties to submit briefs. Instead of considering whether the error prejudiced the accused’s substantial rights under the statutory standard, the Court simply applied its precedents without resolving the underlying issue. By acknowledging NIMJ’s amicus brief and explaining its contents, the CAAF appears to be inviting litigation as to the appropriate standard for determining prejudice in judicial disqualification cases: Is prejudice in judicial disqualification cases determined by applying Article 59(a), UCMJ, or the three-factor Liljeberg test. On the other hand, the amicus brief put the issue squarely before the Court and, without even seeking the views of the parties, the CAAF punted—not exactly encouragement for those considering filing amicus briefs.

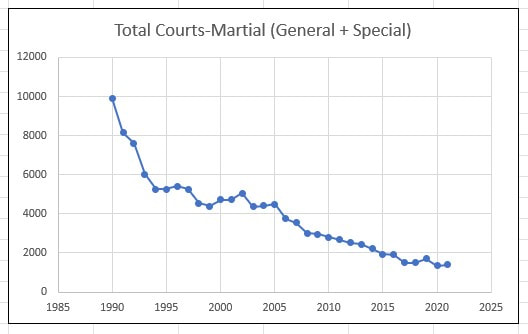

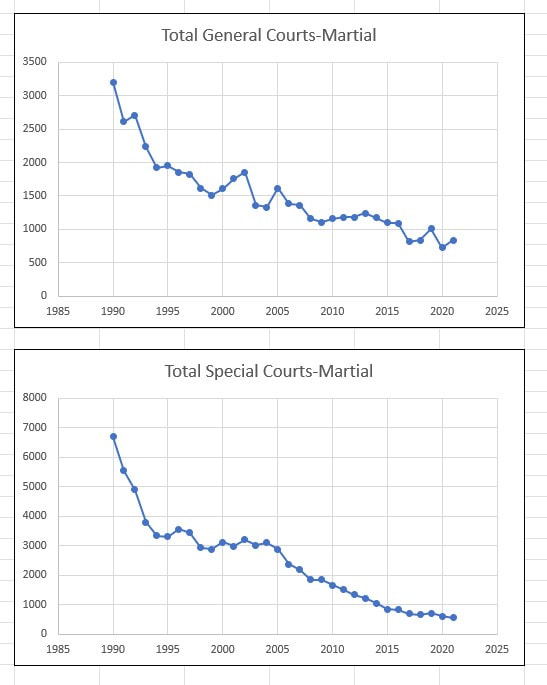

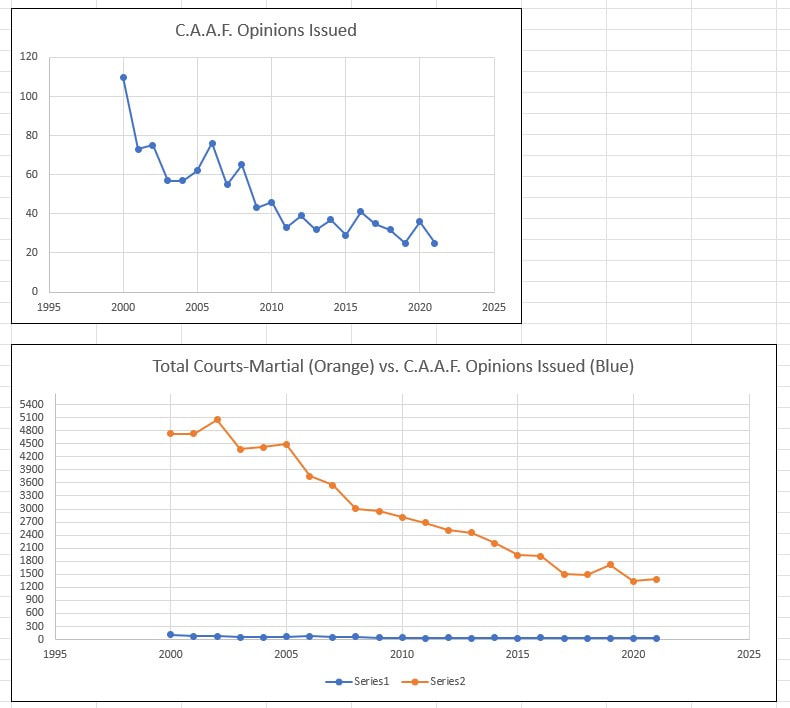

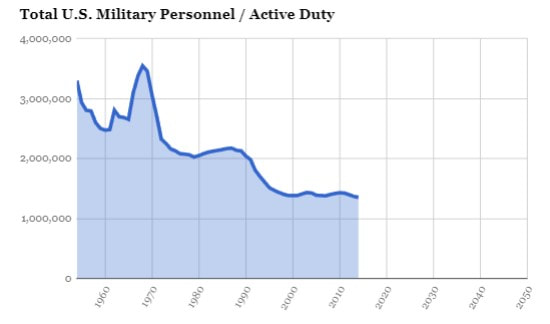

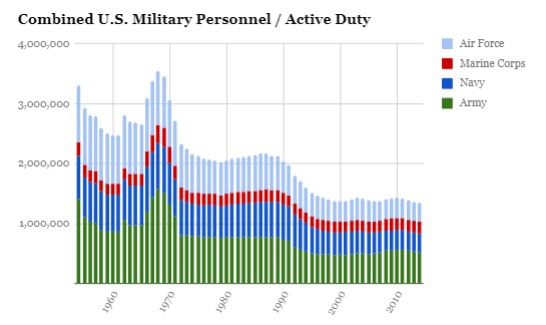

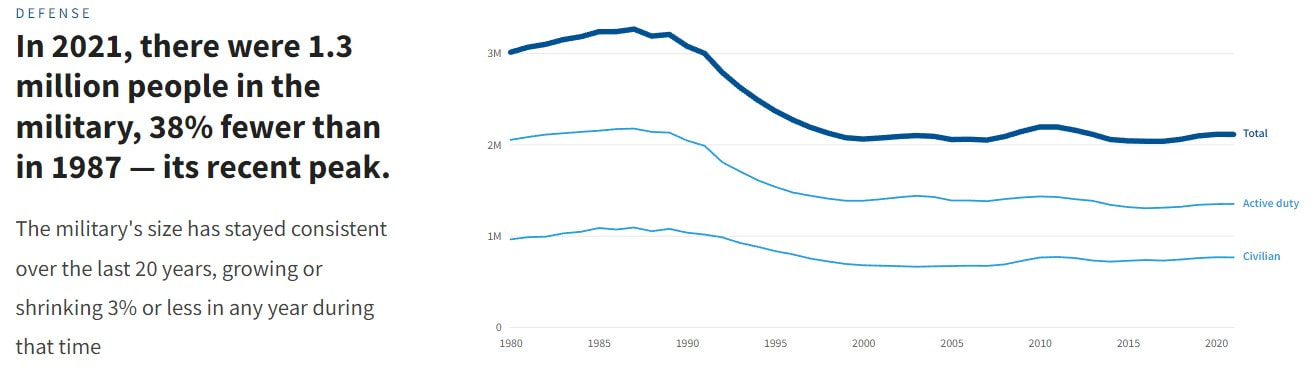

At NIMJ we found someone to give us a picture of military justice over the years. Note, the source for the total strength numbers is David Coleman, U.S. Military Personnel 1954-2014, and is used for a quick WAG comparison, or there is USA Facts. NIMJAll credit goes to NIMJ Extern Jake Dianno. CAAF has granted the petition in United States v. Brown, on a question that asks

ARE APPELLANT'S CONVICTIONS UNDER ARTICLE 91 LEGALLY INSUFFICENT WHERE THERE IS AN ABSENCE OF EVIDENCE THAT THE CHARGED CONDUCT OCCURRED IN THE SIGHT, HEARING, OR PRESENCE OF THE ALLEGED VICTIMS WHILE THEY WERE IN THE EXECUTION OF THEIR OFFICE? The CGCCA published opinion is here. "We hold that sending a disrespectful text message directly to the victim is actionable under Article 91, UCMJ." Some of us have argued, unsuccessfully, that a military judge should allow the defense at least three peremptory challenges of prospective panel members. The argument is based on the idea that the convening authority (the prosecution) has unlimited peremptory challenges because of the members selection process. Alternatively, why should the trial counsel have any peremptory challenge if the convening authority has already said the members are good to go? Some have suggested the liberal grant mandate is a way to accommodate the imbalance. But to get an implied bias challenge you must still present some reasons for granting the challenge.

Today we came across Peter G. Berris, CONG. RSCH. SERV. R47259, Batson v. Kentucky and Federal Peremptory Challenge Law, for a Sunday read. In United States v. Covitz, the Appellant gets a new trial because the military judge abused his discretion in "by denying challenges for cause against multiple panel members." "Appellant’s convictions arose from allegations he assaulted his former girlfriend." Beginning with 14 prospective members, agreement and challenges whittled that down to ten. But the defense had four more challenges (one of which was later resolved with a peremptory challenge)--all initially denied. AFCCA agrees that one denial was proper, so we are down to three. 1. Implied bias challenge based on "based on his knowledge of both Appellant and Maj RW, whom trial defense characterized as “a central witness[.]” ” Trial defense counsel pointed to Maj MP’s “very high opinion” of Maj RW and told the military judge that Maj RW was “very financially well off” based upon some profitable investments he had made. The relevance of Maj RW’s financial status, according to trial defense counsel, was that Maj MP essentially said he “goes to [Maj RW] for financial advice. . . . It’s where [Maj MP] is literally going to somebody who has had a significant amount of success financially and both [sic] in his career and asked him for advice.” Trial defense counsel argued that Maj MP was relying on Maj RW’s advice on “potentially major life and financial decisions.” Trial defense counsel pointed to the length of the conversations and the fact that Maj MP and Maj RW had a long conversation just days before the court-martial, as well as the fact that Maj RW was an adverse witness to Appellant—in no small part because Maj RW was in a relationship with Ms. CC, Appellant’s former girlfriend and victim in the case. The Defense also noted Maj RW’s affiliation with the potential defense witness, Capt SS. The Government opposed because "that because Maj MP knows Appellant, a Government witness (Maj RW), and a Defense witness (Capt SS), that outside observers “would see that as potentially balancing out in a way.” When denying the challenge the MJ said he had considered the liberal grant mandate and that he did “not find it to be a particularly close call based upon [witness/member] limited interaction. 2. The member had apparently rented a home from the Appellant (where the alleged offenses happened) and he had a sister-victim. A question came up about the members knowledge of the house layout and some "sound barrier" problems which migh tbe relevant in testimony. The MJ responded similarly to #1. 3. Same result as #1, 2, based on [A]pproximately eight months before Appellant’s court-martial, she started volunteering at a local shelter for women who were victims of domestic violence. Maj JR’s role was to lead hour-long yoga classes once or twice a month. The shelter prohibited volunteers from talking to the shelter residents about the abuse they suffered and from interacting with the women at all outside the shelter. [S]he went through a four-hour volunteer orientation at the shelter before she started leading the yoga classes, but there was no discussion of domestic violence itself during the orientation. The Defense challenged Maj JR under an implied bias theory based upon her volunteering at the shelter. Trial defense counsel said the Defense might call an expert witness to testify about “biases within the system when they know the victim of domestic violence,” which might conflict with Maj JR’s experience at the shelter. The Government perempted a different member and the defense perempted #3 above.

Thus, there were eight members and quorum. The AFCCA concludes that the MJ erred as to #1 and #2 above. There is a good analysis of the implied bias and liberal grant mandate. It seems the AFCCA takes the position that the decision was a close call on the facts and the liberal grant mandate should have resulted in a granted challenge. |

Disclaimer: Posts are the authors' personal opinions and do not reflect the position of any organization or government agency.

Co-editors:

Phil Cave Brenner Fissell Links

SCOTUS CAAF -Daily Journal -2024 Ops ACCA AFCCA CGCCA NMCCA JRAP JRTP UCMJ Amendments to UCMJ Since 1950 (2024 ed.) Amendments to RCM Since 1984 (2024 ed.) Amendments to MRE Since 1984 (2024 ed.) MCM 2024 MCM 2023 MCM 2019 MCM 2016 MCM 2012 MCM 1995 UMCJ History Global Reform Army Lawyer JAG Reporter Army Crim. L. Deskbook J. App. Prac. & Pro. CAAFlog 1.0 CAAFlog 2.0 Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed