|

Recently, ProPublica published an article about sexual assault investigations and prosecutions--or lack of prosecution. Vianna Davila, Lexi Churchill and Ren Larson, ProPublica and The Texas Tribune, and Davis Winkie, Military Times, The Army Increasingly Allows Soldiers Charged With Violent Crimes to Leave the Military Rather Than Face Trial. Pro Publica, 10 April 2023. Today, we are receiving news from Task & Purpose about the decline in prosecutions. Jeff Shogol, Pentagon reports huge drop in troops court-martialed for sexual assault over last 10 years. Task & Purpose, 27 April 2023. I was struck by this comment: A major reason for the drop in courts-martial is that sexual assault survivors have shown they prefer other ways to adjudicate their cases, said Nate Galbreath, acting director of the Department of Defense Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office. One option for off-base offenses (or those with shared local and federal jurisdiction over the base) is for the local prosecutor to have the case for disposition. Or if on a base with exclusive federal jurisdiction, could not the USA prosecute?

See, e.g., Chap 10, AFI 51-201. Fink v. Y.B. and the United States.In the pending general court-martial of United States v. Fink, the military judge ruled that Seaman (SN) G.C. may testify that he had a sexual encounter with Petitioner a few months prior to the accused’s alleged assault of Petitioner. The prior alleged encounter has no connection to the charged sexual assault other than to contradict statements made by Petitioner. Petitioner asks this Court to issue a writ of mandamus requiring the military judge to exclude this evidence under Military Rule of Evidence (M.R.E.) 412, Manual for Courts-Martial, United States (2019 ed.). We conclude Petitioner is entitled to relief and grant the writ. Y.B. v. United States and Fink--CGCCA. Fink then takes a writ appeal petition to CAAF raising three issues, only one of which CAAF has decided. Two issues have been left for decision in course of ordinary review should there be a conviction. I. Whether this Court has jurisdiction to review a writ-appeal petition filed by an accused to review the decision of a court of criminal appeals on a petition for extraordinary relief filed under Article 6b. [GRANTED] When granting on the first issue, CAAF asked the Government, Appellant, and the named victim for additional briefing on two questions related to Randolph v. HV, 76 M.J. 27, 30-31 (C.A.A.F. 2017), which held that this Court does not have jurisdiction to hear the appeal of an accused in the circumstances of this case. These two questions were whether the amendment of Article 67(c), UCMJ, in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, Pub. L. No. 114-328, § 5331, 130 Stat. 2000, 2934-35 (2016) [hereinafter the 2017 NDAA], requires this Court to reconsider its holding in Randolph, and whether Article 67(a)(3), UCMJ, 10 U.S.C. § 867(a)(3) (2018), now provides this Court jurisdiction. After working through the reasons for its decision in Randolph, the court finds jurisdiction and that Randolph has been superseded by the statutory changes for "cases in which the amended Article 67(c)(1)(B), UCMJ, applies."

United States v. PullingsPullings pled guilty to sexual assault of a child and sexual abuse of a child specifications and was sentenced to thirteen years of confinement, reduction to E-1, total forfeitures, and a dishonorable discharge. Based on the pretrial agreement, the convening authority approved only eight years of confinement and disapproved the total forfeitures. The issue Pullings raised involved the conditions of his post-trial confinement. As is common at many bases, the Air Force paid a local jail to serve as the confinement facility for pending transfer to another military facility. Pullings raised violations of Article 55, UCMJ and the Eighth Amendment. His claims of cruel and unusual punishment referenced a number of distinct complaints, including contaminated drinking water, moldy food, food poisoning, sewage water leaking into his cell, broken toilets, lack of sunlight, withholding of pain medicine, medication for depression and anxiety, and failure to alleviate symptoms from Raynaud’s Syndrome. Pullings sent various complaints both to the civilian confinement facility and to his Air Force chain-of-command. Pullings submitted declarations and the government submitted its own declarations, but AFCCA decided it did not need to order a DuBay hearing to make findings of fact because even if the documentary evidence submitted contained inconsistencies, resolving those disputes in Appellant’s favor would not result in relief to Appellant under the cruel and unusual punishment caselaw. The case raised appellate review questions because Pullings did not raise his confinement conditions in his post-trial submissions to the convening authority, so they were not part of the record. Judge Maggs opinion declined to address whether it was appropriate to consider matters outside the record or not because the result of the case would be the same regardless. CAAF also agreed that there was no need for a DuBay hearing for further fact finding. CAAF then looked at the merits of the Eighth Amendment and Article 55 claims and determined that Pullings had not shown government officials acted with deliberate indifference. Judge Hardy concurred. He wrote separately to address a topic that comes up frequently in CAAF’s cases over the last several years, the scope of CAAF’s ability to consider the case in the first place. Judge Hardy focused on United States v. White, 54 M.J. 469 (2001) which explicitly found CAAF had the jurisdiction to consider post-conviction Eighth Amendment claims. The White court determined Article 67 gave CAAF jurisdiction because the statutory grant of authority “with respect to the findings and sentence” encompassed more than the authority merely to affirm or set aside a sentence, but that it also included the authority to ensure the severity of the adjudged and approved sentence was not unlawfully increased by prison officials and that it was carried out in a way that did not violate Article 55 and the Eighth Amendment. A unanimous White court based its decision in part on the fact that the Feres doctrine denied servicemembers civil remedies for constitutional violations. Judge Hardy took direct aim at White, arguing that as an Article 1 court and under Clinton v. Goldsmith, 526 U.S. 529 (1999), CAAF lacked the ability to expand its congressional grant of authority. Simply put, because Pullings’ complaints involved post-trial conditions, CAAF lacked jurisdiction to consider them. Judge Hardy left open the question whether the CCAs could consider post-trial confinement claims, but opined that they could not under Article 66(d)(1)(A). Judge Hardy considered stare decisis and reasoned that White should be overruled because it was poorly reasoned, is unworkable, that there are no reliance interests undermined by overturning White, and that overturning White would not undermine public confidence in the law. Interestingly, Judge Hardy references the Feres doctrine issue and quotes Justice Scalia opining that “Feres was wrongly decided. . . .” United States v. Johnson, 481 U.S. 681, 700-01 (1987) (Scalia, J, dissenting). But Judge Hardy acknowledges that Feres remains good law and he simply concludes even if Feres is not overruled, that does not justify a judicially created scheme that gets around Article 67’s statutory bounds. Jason Grover Counterman v. ColoradoOn 19 April 2023 the court will hear oral argument on this issue:

Whether, to establish that a statement is a "true theat" unprotected by the First Amendment, the government must show that the speaker subjectively knew or intended the threatening nature of the statement, or whether it is enough to show that an objective "reasonable person" would regard the statement as a threat of violence. SCOTUSblog link. Ashley Merryman, The Dangerous Cycle of Pentagon Sexual Assault and Harassment ‘Lowest Level’ Policy. LawFare, 12 April 2023.

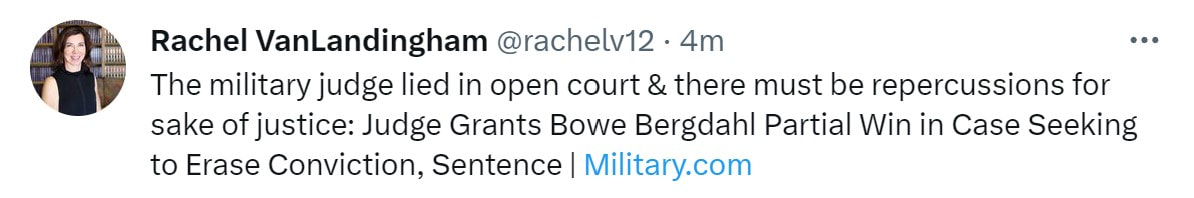

The report is linked in the article, and this link should take you to the report also. Judge Grants Bowe Bergdahl Partial Win in Case Seeking to Erase Conviction, Sentence

"[Judge] Walton granted Bergdahl's motion for a summary judgment on the soldier's claim that the military judge who presided over his case did not disclose that he had applied for a civilian position at the Justice Department while the court-martial was underway -- a failure that Bergdahl argues denied him a fair trial." One take: United States v. LoveLove is a reminder that Grosty issues can sometimes get attention, although not always much love. Appellant asserts three errors before this court, none of which merits discussion or relief. Pursuant to United States v. Grostefon, 12 M.J. 431 (C.M.A. 1982), appellant asserts nine errors before this court, one of which merits discussion but ultimately no relief. The court notes the error is a repeat from the prior iteration of the rule. This court addressed a nearly identical issue under a prior version of the rule in United States v. Cornelison, 78 M.J. 739 (Army Ct. Crim. App. 2019). Appellant contends, in light of Cornelison, it was error for the military judge to allow the government to conduct direct examination of the victim's unsworn statement under R.C.M. l00l(c). While we agree that it was error, the error was forfeited when appellant did not object. See Cornelison, 78 M.J. at 742 n.2. For various reasons the Cornelison court found no prejudice partly because the prosecution argued for 30 years confinement but the members adjudged 18 months.

United States v. LaraLara pled guilty to one specification of attempt to view CP and one specification of willful dereliction of duty for failing to refrain from storing, processing, displaying, and transmitting pornography, sexually explicit material, or sexually oriented material while on duty. The military judge sentenced him to 12 months and a BCD. Prior to trial and while discussing the PTA, his ADC advised him he would not have to register for the attempted CP viewing. During providency, the MJ also advised him he would not have to register. So, off to the Brig. The court finds the GP improvident and sets aside the findings and sentence and allows a rehearing. When Appellant was released from confinement, he received a document entitled, “United States Probation System Offender Notice and Acknowledgment of Duty to Register as a Sex Offender.” This document indicated Appellant had to register as a sex offender under the federal requirements, pursuant to the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act of 2006 (SORNA) codified at 34 U.S.C. § 20901, and he had to register as a sex offender in any state in which he resided. The court explains that There are three different, but interrelated, aspects of sex offense registration pertinent to this case: (1) the federal statute (34 U.S.C. § 20901, et seq.) which requires mandatory sex offender registration for those who are convicted of offenses within the statute’s scope; (2) DoDI 1325.7 which identifies offenses that trigger mandatory sex offender reporting; and (3) state laws concerning registration for qualified sex offenses. See United States v. Miller, 63 M.J. 452, 459 (C.A.A.F. 2006)[.] Additionally, trial “defense counsel must be aware of the federal statute that requires mandatory reporting and registration for those who are convicted of offenses within the statute’s scope, as well as DoDI 1325.7, which identifies offenses that trigger mandatory sex offender reporting.” Trial defense counsel should also state on the record of the court-martial that counsel has complied with this advice requirement.” "While failure to so advise an accused is not per se ineffective assistance of counsel, it will be one circumstance [an appellate c]ourt will carefully consider in evaluating allegations of ineffective assistance of counsel.” However, “[g]iven the plethora of sexual offender registration laws enacted in each state, it is not necessary for trial defense counsel to become knowledgeable about the sex offender registration statutes of every state.” The court finds the SORNA required registration here. Because Appellant was misadvised the GP is improvident and set aside, and there can be a rehearing.

Consider visiting SMART operated by DOJ and viewing the National Guidelines and 34 U.S.C. 20911(7)(G). 20911 lists possession, production, and distribution but not viewing. Attempt to do is listed elsewhere. Certainly SORNA is meant to be expansive. Query, is an attempt to view a registration offense under SORNA? Is there actually some ambiguity. We'd be happy to hear from those more informed. District Court for the District of Columbia“LADARION D. STANTON Petitioner, v. JAMES A. JACOBSON Major General, U.S. Air Force, UNITED STATES, et al., Respondents” Stanton v. Jacobson, Civil Case No. 19-699 (RJL), (D.D.C. Apr. 3, 2020). Petitioner Ladarion Stanton ("Stanton" or "petitioner"), a former airman in the United States Air Force, seeks collateral review of his conviction for petty larceny and the punishment of "no sentence" imposed by the military justice system. Respondent Major James Jacobson ("Jacobson") was the "Convening Authority" of Stanton's general court-martial and imposed the sentence on Stanton after his case wended its way through the military appeals process. (The other respondent is the United States.) The gravamen of Stanton's petition is that, after his earlier convictions on several unrelated charges were overturned and remanded to Jacobson for retrial and resentencing, Jacobson accepted Stanton's offer to resolve his case via a "discharge in lieu of court-martial." Stanton believed this resolution would not only result in vacating the charges overturned on appeal but also the charge of larceny, to which he had already pled guilty and which had already been affirmed. Stanton also believed the discharge would leave the military without any jurisdiction over him. Although respondents acknowledge, as an administrative matter, that Stanton was discharged when Jacobson accepted Stanton's discharge in lieu of court-martial, they nonetheless contend that this discharge had no effect on Stanton's larceny conviction. Indeed, they insist that the military has retained jurisdiction over Stanton's court-martial. The parties' cross-motions for summary judgment are now ripe. After extensive briefing and with the benefit of oral argument, I have concluded that Stanton's larceny conviction did survive his administrative discharge. Therefore, I GRANT respondents' motion for summary judgment, DENY petitioner's motion for summary judgment, and DISMISS petitioner's petition for habeas corpus. |

Disclaimer: Posts are the authors' personal opinions and do not reflect the position of any organization or government agency.

Co-editors:

Phil Cave Brenner Fissell Links

SCOTUS CAAF -Daily Journal -2024 Ops ACCA AFCCA CGCCA NMCCA JRAP JRTP UCMJ Amendments to UCMJ Since 1950 (2024 ed.) Amendments to RCM Since 1984 (2024 ed.) Amendments to MRE Since 1984 (2024 ed.) MCM 2024 MCM 2023 MCM 2019 MCM 2016 MCM 2012 MCM 1995 UMCJ History Global Reform Army Lawyer JAG Reporter Army Crim. L. Deskbook J. App. Prac. & Pro. CAAFlog 1.0 CAAFlog 2.0 Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed