|

The Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has affirmed a lower court’s finding that a claim under the FTCA is not Feres barred when the claim relates to a sexual assault committed by a servicemember against a servicemember. See Spletsoser v. Hyten. The issue arose when the Government argued that Feres barred the claim. The 9th rehearses Feres and its progeny in a helpful manner. Essentially, the court concludes that a sexual assault is not incident to service, an “alleged sexual assault [could] not conceivably serve any military purpose.”

It’s not clear exactly how long a man who called himself Barry O’Beirne lived a quiet life in Daly City, the sleepy suburb a few miles south of San Francisco. It’s also not clear what he was doing on the morning of Wednesday, June 6, 2018, when, after 35 years, Air Force special agents knocked on his door and arrested him for desertion. When arrested he denied being a spy, explained he'd changed his name and had simply left because of depression with his life. He stayed in California under his assumed name. The jigsaw puzzle of William Howard Hughes Jr.'s life has many missing pieces. After disappearing into thin air in 1983 he was wanted across the globe by numerous agencies, from the Air Force to the FBI to Interpol. At one point it was thought that he defected to the Russians. Some suggested he sabotaged the disastrous Challenger space shuttle launch. Even after his recent capture, much of this unlikely story remains a mystery for the ages. Here’s what we found out. Update: Defense News reports that the Senate has gone on vacation for a month, with Tia Johnson and others confirmation being held. Update: Page S3731 of the July 28, Congressional Record, shows Senator Reed asking for unanimous consent to confirm Tia Johnson's nomination to CAAF. On page S3732, after Senator Reed discussed the importance of confirming the nomination, Senator Hawley objected. Senator Reed then moved for unanimous consent for an executive session to debate the nomination. Senator Hawley objected. https://www.congress.gov/117/crec/2022/07/27/168/125/CREC-2022-07-27.pdf The CAAF has operated with only four active judges since C.J. Stuckey retired. The court has been asking senior judges to sit in for granted cases.

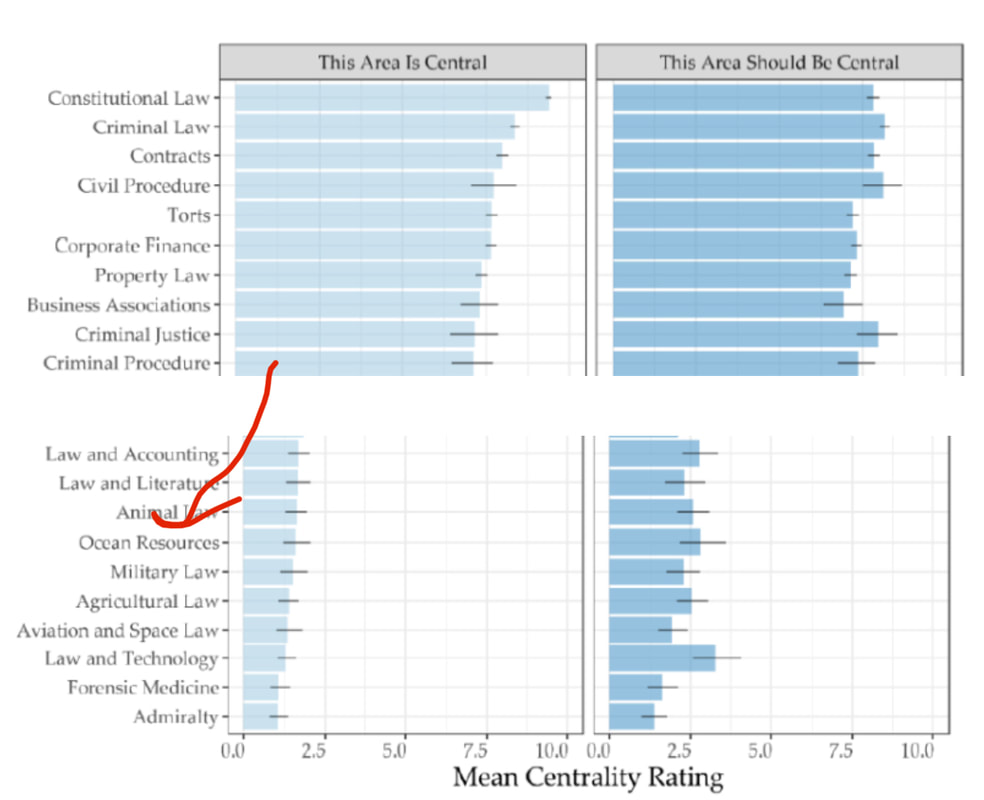

Gene Fidell has been monitoring and commenting on the affect of four v. five because petitioners, he argues, have a significantly lower chance of getting a grant with four vice five judges. See, e.g., here and here To date, 257 petitioners been affected. President Biden has nominated Tia Johnson as the fifth CAAF judge. But her nomination has been held up. One potential explanation can be found in Raju and Cole, Hawley says he'll hold up State and Defense Department nominess unless Blinken and Austin resign. CNN, September 14, 2021; see also, here (hawley.senat.gov); Jack Suntrap, White House criticizes Missouri Sen. Hawley for delaying Defense confirmations. Union-Bulletin, July 20, 2022 (noting Tia Johnson had cleared the Senate committee in March/April). Sometimes it's good to keep things in perspective. A major survey of the American law professoriate just dropped its results. One question asks for the respondent's opinion of the "centrality" of a given subject, and whether it should be more central. Over 100 areas of law were included. Military law ranked 6th from the bottom--below both animal law and ocean law. However, the professoriate considers military law to be more "central" than admiralty law. Brenner FissellIn Bench, (the 21st published opinion this term) the issue was [W]hether Appellant’s right to be confronted by a complaining witness was violated when trial counsel misled Appellant’s son by telling him that Appellant was not watching his son’s remote live testimony. Because Appellant failed to preserve this issue at trial, the Court must decide whether any error was plain or obvious. We hold that it was not. [corrected] The court first discussed but did not find waiver of the issue. The court proceeded to a plain error analysis. The Government more reasonably argues that Appellant waived this issue by operation of law under the plain language of Rule for Courts-Martial (R.C.M.) 905(e) (2016 ed.). That rule provides that such claims “must be raised before the court-martial adjourned for that case and, unless otherwise provided in [the Manual for Courts-Martial, United States], failure to do so shall constitute waiver.” R.C.M. 905(e). We acknowledge that the language of the rule would appear to be dispositive on this point in the Government’s favor, but as this Court has recognized in the past, there has long been disagreement in our own precedent about whether the word “waive[d]” in R.C.M. 905(e) actually means “waived” (as defined by the Supreme Court in Olano, 507 U.S. at 733), or instead means “forfeited” (the failure to preserve an issue by timely objection). See Hardy, 77 M.J. at 441–42 (noting the disagreement in this Court’s precedents); id. at 445 (Ohlson, J., dissenting) (same). Two of our more recent precedents lead us to conclude that regardless how one interprets the word “waive[d]” in R.C.M. 905(e), that rule does not extinguish a claim when there has been plain error. Half a Precedent Is No Precedent At AllWhy the application of military law to half-pay officers in Britain from 1749 to 1751 does not support the perpetual application of military law to retirees of the Armed Forces of the United States In Larrabee, the D.C. Circuit supported its holding that military retirees are subject to status-based military law jurisdiction with references to eighteenth-century historical practice. The majority’s primary historical example is that of half-pay officers. According to the majority, the subjugation of half-pay officers to military law in Britain from 1749 to 1751 demonstrates the Framers’ acceptance that military justice may be applied to members of the land and naval forces who are not in active service. In this post, I will make two critiques of the court’s analysis. First, the majority improperly discounts the vigorous debates over whether to subject half-pay officers to military justice. The majority treats these debates as policy questions. But these debates were, in fact, constitutional debates about the legitimacy of applying military law to those not in active service. Second, although Parliament briefly subjected half-pay officers to military justice, the majority fails to establish that this brief action settled the legitimacy of applying military law to retired officers in Britain. If anything, the debates surrounding half-pay officers show the opposite: that after a period of vigorous debate, the British rejected applying military law to retired officers. A fortiori, the majority fails to show that our Framers accepted the constitutional legitimacy of applying military law to those not in active service. Unlike in Britain, neither Congress nor state/colonial legislatures subjected military personnel to military law when they were not in active service. I am not aware of any evidence (and the majority provides none) suggesting that the Framers accepted the legitimacy of such a practice.

Update Monday, August 8, 2022 Appeal - Summary Disposition No. 22-0023/AR. U.S. v. Michael L. McClure. CCA 20190623. On further consideration of the granted issue, 82 M.J. 194 (C.A.A.F. 2022), and in light of United States v. Mellette, __ M.J. __ (C.A.A.F. July 27, 2022), we conclude that even assuming some error by the military judge, Appellant was not prejudiced. Accordingly, it is ordered that the judgment of the United States Army Court of Criminal Appeals is affirmed. Following the Supreme Court’s proviso in Trammel v. United States Trammel, 445 U.S. 40, 50 (1980) that evidentiary privileges are to be strictly construed, the CAAF holds in a 3-2 opinion in Mellette that the M.R.E. 513(a) psychotherapist-patient privilege does not extend to behavioral health diagnoses and treatments contained within medical records or some other form not consisting of communication between a patient and a psychotherapist or psychotherapist’s assistant. CAAF’s ruling resolves a circuit split between the land and sea forces in favor of the Army appellate court’s minimalist approach. In 2006 the Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals took an expansive view of the M.R.E. 513 privilege. See H.V. v. Kitchen, 75 M.J. 717 (CGCCA 2016). In 2019, in an unpublished opinion the Army Court of Criminal Appeals followed the dissent in Kitchen by finding that mental health diagnoses and treatments are independent of confidential communications and significantly are often meant to be disclosed to a third party, such as a pharmacist or a physician prescribing a medication for a physical ailment (United States v. Rodriguez, 2019 CCA LEXIS 387). (Disclosure: this writer was Rodriguez’s appellate counsel.) In 2021 the Navy Court of Criminal Appeals followed the Coast Guard’s more expansive view of the M.R.E. 513 privilege in in its ruling in United States v. Mellette (81 M.J. 681). The CAAF granted certoriari, specifying three issues relating to the M.R.E. 513 privilege and here we are. (Notably, the Air Force Court of Criminal Appeals had not weighed in on the issue but anecdotally, Air Force counsel and trial judges have followed the expansive interpretation of the privilege until now.) In Mellette, the CAAF granted review of three issues: a. Are diagnoses and treatment records subject to the M.R.E. 513 privilege? b. Should the NMCCA have reviewed the mental health records before ruling? c. Was there a waiver of the M.R.E. 513 privilege in the case? Deciding the first issue in favor of the petitioner, the second and third issues are not reached. CAAF’s holding centers on both Trammel’s prescription that evidentiary privileges “must be strictly construed.” Examining the specific language of M.R.E. 513(a), the court finds that the limiting language of “communication” and “between the patient and a psychotherapist” are meaningful choices. The court notes that in contrast the analogous Florida state statute explicitly protects both communications and records, unlike M.R.E. 513. Turning to a government argument that the M.R.E. 513 privilege is akin to the attorney/client privilege in M.R.E. 502, the court dismisses this argument by noting that first, the protection for attorney work product is a separate rule (R.C.M. 701(f)) without an equivalent rule for psychotherapist work product; and second, that the attorney-client privilege is in fact narrow and does not include the underlying facts that may be communicated with an attorney (citing to Upjohn Co, 449 U.S. 383, 395 (1981) and In re Six Grand Jury Witnesses, 979 F.2d 939, 945 (2d Cir. 1992)). In the dissent, Judge Maggs (joined by Judge Sparks) argues that diagnoses and treatment are privileged under M.R.E. 513(a) “only to the extent that they reveal confidential communications between the patient and psychotherapist that were made for the purpose of diagnosing or treating the patient’s mental condition.” Had this been the majority opinion, the practical effect may well have been to force in camera review of medical records, deny the disclosure of specific diagnoses and allow the production of medication records (as few medications are prescribed for one and only one behavioral health condition). Of note to trial practitioners, the CAAF finds with respect to the specific mental health records at issue in Mellette that the sought records “to include the dates visited said mental health provider, the treatment provided and recommended, and her diagnosis….were not protected from disclosure by M.R.E. 513(a)” and that these records should have been produced and potentially admitted. As well, the court also reiterates that diagnoses and evidence that relate to a witness’ credibility and reliability are material to the defense. One would expect that going forward defense discovery requests for AHLTA and similar records will request the same specific three categories requested in Mellette. Although on its face CAAF’s decision in Mellette may appear to buck against the trend of expanding victims’ rights, it actually follows the contemporary judicial path of construing privileges narrowly in order to preserve the truth-seeking purview of the tribunal. The decision falls in line with Harpole (77 M.J. 231)(narrowing the victim-advocate privilege), Jasper (72 M.J. 276)(narrowing the clergy-parishioner privilege), and Durbin (68 M.J. 271)(narrowing the spousal privilege). Nathan Freeburg, a guest post.Readers are invited to offer guest posts by emailing us at admin@nimj. org. Three Statuses, not Two: Why Larrabee Is the Wrong Rule for Nonprofessional SoldiersIn recent years, the military has court-martialed military retirees for conduct that occurred off base and after retirement. These courts-martial involve civilian offenses (e.g., sexual assault) when the servicemen have essentially returned to civilian life. Congress has authorized such prosecutions under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. But there have been challenges to whether Congress has the constitutional authority for such broad military jurisdiction. On Tuesday, the D.C. Circuit in Larrabee v. Del Toro upheld the constitutionality of Congress’s authorization, holding that a military retiree remained part of the land or naval forces. This is an incredibly difficult legal issue, and I am uncertain about the right bottom line. But I want to flag a very important constitutional issue that has gotten lost in the analysis: the special constitutional restrictions on subjecting nonprofessional soldiers to military law. A quick background on the facts of this case. Steven Larrabee is a former active-duty Marine. He retired from the military after twenty years. He worked as a civilian employee on a military base in Japan, and he also managed two bars part-time. After he had retired from the military, Larrabee sexually assaulted a bartender in Japan. Rather than let Larrabee face charges in a civilian Japanese court, the federal government prosecuted him under the UCMJ for sexual assault and for making a video recording of the assault. He pleaded guilty, but collaterally challenged his military conviction. In the Marine Corps, retirement occurs in two stages. First, after 20 years of service, a person may transfer to the “Fleet Marine Reserve.” Then, after 30 years of service (including time spent on the Fleet Marine Reserve list), a Marine may be moved to the retired list. Fleet Marine Reservists and retirees receive pensions for their prior service. The government calls this “retainer pay” for future service, but this is a euphemism. Although Fleet Marine Reservists are theoretically liable to be involuntarily called up in national emergencies, this practically never happens. Additionally, the “retainer pay” is clearly compensation for past services; the amount of the retirement pay is directly correlated with the years of prior service, not with the probability of future recall. In an opinion by Judge Neomi Rao, the D.C. Circuit held that the military could court-martial Larrabee even though he is retired. The court’s argument effectively has three premises. First, the constitutionality of subjecting a person to military jurisdiction “turns ‘on one factor: the military status of the accused’” (op. at 12, quoting Solorio v. United States, 483 U.S. 435, 439 (1987)), so a member of the Armed Forces is subject to military jurisdiction at all times, while a civilian is not. Second, a person falls within the “land or naval forces,” as that term is used in the Constitution, “if he has a formal relationship with the armed forces that includes a duty to obey military orders” (op. at 17). This is the majority’s test for whether to apply status-based jurisdiction. Third, Larrabee had a duty to obey military orders because he could be ordered to reenter active service in a war or national emergency and because he could be required to report for training for up to two months in any four-year period (op. at 25–26, citing 10 U.S.C. § 8385). Therefore, the court concludes, Larrabee was subject to military law at all times, despite being retired. The first premise, however, rests on a false dichotomy. When it comes to the military, Anglo-American law recognizes three statuses, not two: professional soldier, nonprofessional soldier, and civilian. Only professional soldiers may be subject to military law at all times, even when off duty, based solely on their “status” as soldiers. As full-time professionals, these servicemen are always in actual military service. (Being “in service” is not synonymous with “discharging official duties.”) At the opposite end, civilians are not amenable to military law and may not generally be tried by courts-martial. In between these two paradigms, however, is a third status: that of the nonprofessional soldier (e.g., a member of the militia). For these nonprofessional (part-time) soldiers, Anglo-American law has a functional relationship to military justice. Nonprofessional soldiers are subject to military law while in active service and in training; but they are subject to civilian law—and retain their full common-law rights—when they act as civilians. The Constitution’s text reflects this distinction. The Fifth Amendment provides for civilian criminal procedure protections but then has two different military exceptions: the status-based jurisdiction of the professional forces (an exception for “cases arising in the land or naval forces”) and the more functional test applied to nonprofessional soldiers (an exception “in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger”). This distinction reflects centuries of Anglo-American practice, which has subjected professional forces to more extensive military jurisdiction than nonprofessional forces. The D.C. Circuit’s false dichotomy has further consequences. The court says that a person falls within the land or naval forces if the person “has a formal relationship with the armed forces that includes a duty to obey military orders.” But this is too simple. This test might be correct for regular (professional) soldiers; but it is not the right test for nonprofessional soldiers. Both kinds of soldiers have a formal relationship with the military, including the duty to obey orders. Some of the early cases Judge Rao cites involve courts-martial of militiamen, not professional soldiers. See Houston v. Moore, 18 U.S. (5 Wheat.) 1 (1820); Martin v. Mott, 25 U.S. (12 Wheat.) 19 (1827). Like Larrabee, these militiamen were enrolled in a military force pursuant to federal law. Also like Larrabee, they were obligated to obey military orders, including to report for duty if ordered. (In fact, the militiamen in these cases were subject to courts-martial for failing to report for duty.) But members of the militia cannot and have never been subject to sweeping status-based military jurisdiction that lets them be court-martialed for criminal conduct that occurs in their civilian life. The retention of civilian life under civilian law is a core aspect of the nonprofessional armed forces when its members are not in active service. With the proper distinction in view, things get more complicated: To determine whether Larrabee remained in the “land or naval forces,” as those terms were understood at the Framing, the court should have asked whether Larrabee remained a professional soldier or sailor. Today, many might write-off the possibility that Larrabee was effectively a militiaman because he was enrolled in the federal Armed Forces, not a state force or National Guard. But as I explain at length in my forthcoming article Deciphering the Armed Forces, the distinction between “armies” and “militia” is not one of federalism. Rather, the proper constitutional distinction between these forces has to do with professionalism: the “armies” (or “land forces”) are the regular, professional forces, while the militia comprises nonprofessional citizen-soldiers. The constitutional question about how far Congress may extend military law has become immensely complicated because of Congress’s efforts to evade the limitations of the Militia Clauses. The Constitution contemplates that Congress may exercise plenary authority over the armies and navy (the professional forces). But the Constitution gives Congress only a very limited power to call forth the militia, and power over the militia is shared with the states. To evade these limitations, Congress created the military reserve system in the twentieth century. These reservists are citizen-soldiers, and the organized reserves operate as a de facto nationally organized and controlled militia. Because reservists are essentially militiamen, Congress should not be allowed to extend military law to off-duty reservists. The federal reserve forces may be an unconstitutionally organized national militia; but for Fifth Amendment purposes, they should still be a militia. Here is where it gets even more complicated for Larrabee’s case. The Fleet Marine Reserve is not part of the organized reserves of part-time citizen-soldiers. Instead, it is a component to which retirees of the regular Marine Corps go. Many facts cut in favor of recognizing Larrabee as a member of the professional forces. The Fleet Marine Reserve is restricted only to former full-time Marines. These Marines entered service voluntarily. They have completed a full career in the Marines. Further, they have elected to remain on the rolls and continue to draw pay and hold their military rank. (Marines could elect for discharge, although they would forfeit their retirement pay by doing so.) But many facts also cut the other way. Once transferred to the Fleet Marine Reserve, these Marines do not have the power and duties ordinarily vested in regular forces. As Larrabee pointed out in his brief (written by Professor Steve Vladeck), these retirees “[l]ack authority to issue binding orders,” cannot be promoted, do not “participate in any military activities,” and may not serve on courts-martial (pp. 25-26). Functionally, they act as a pool of available emergency military manpower, not as professional soldiers. This makes Fleet Marine Reservists more like militiamen than regular soldiers. Making this issue even harder, Larrabee was a Marine, not an Army soldier. The Marines are a maritime land force. Constitutionally, I am uncertain whether they should fall within the “armies” or “navy.” (Federal law defines Marines to be part of the naval service, but it is less clear whether that is their status under the Constitution.) The militia is a force that fights on land, and for reasons I explain in this article (see p. 1001 n.56), I am skeptical that part-time seamen fall within the constitutional militia. Congress may have more power to govern part-time sailors (who still fall within the plenary federal naval power) than it has over part-time land soldiers (who are effectively militiamen). So Larrabee’s case might plausibly fall within Congress’s power to discipline members of the navy, even if Congress’s power would be more restricted over a comparably situated retired land soldier. For these reasons, I am deeply unsure what the correct judgment in this case should be. Laying that complication aside, however, one cannot properly analyze this legal issue without keeping in mind the status of nonprofessional soldiers. By omitting nonprofessional soldiers from their analysis, the majority announced a test that begged the critical question. That question was not whether Larrabee retained some affiliation with the Armed Forces. He obviously did. Instead, the critical question was whether Larrabee remained a member of the professional forces, despite having retired and returned to civilian life. Only if he remained a professional could the federal government apply military law to him solely on the basis of his status as a member of the Armed Forces. Robert LeiderAssistant Professor, George Mason University, Antonin Scalia Law School Yes, we have noticed Mellette is out and will have a comment by Monday. Word is that there are now several ongoing cases where the defense is asking the MJ to reconsider Mil. R. Evid. 513 rulings in light of Mellette. The trailer-park expands.

No. 22-0165/AF. U.S. v. Jonathan M. Martinez. CCA 39973. On consideration of the petition for grant of review of the decision of the United States Air Force Court of Criminal Appeals, it is ordered that said petition is granted on the following issue: WHETHER, BY DENYING APPELLANT'S MOTION TO INSTRUCT THE PANEL THAT A GUILTY VERDICT REQUIRED UNANIMITY, THE MILITARY JUDGE VIOLATED APPELLANT'S FIFTH OR SIXTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS. No. 22-0196/NA. U.S. v. Isiah Anthony P. Causey. CCA 202000228. On consideration of the petition for grant of review of the decision of the United States Navy-Marine Corps Court of Criminal Appeals, it is ordered that said petition is granted on the following issue: DO MILITARY DEFENDANTS HAVE A RIGHT TO UNANIMOUS VERDICTS FOR SERIOUS OFFENSES TRIED AT COURTS-MARTIAL, IN LIGHT OF RAMOS v. LOUISIANA, 140 S. CT. 1390 (2020)? |

Disclaimer: Posts are the authors' personal opinions and do not reflect the position of any organization or government agency.

Co-editors:

Phil Cave Brenner Fissell Links

CAAF -Daily Journal -2024 Ops ACCA AFCCA CGCCA NMCCA JRAP JRTP UCMJ Amendments to UCMJ Since 1950 (2024 ed.) Amendments to RCM Since 1984 (2024 ed.) Amendments to MRE Since 1984 (2024 ed.) MCM 2024 MCM 2023 MCM 2019 MCM 2016 MCM 2012 MCM 1995 UMCJ History Global Reform Army Lawyer JAG Reporter Army Crim. L. Deskbook J. App. Prac. & Pro. CAAFlog 1.0 CAAFlog 2.0 Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed